Napoleon at Waterloo: Dysuria and Defeat

Sara Best, MD

The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 was the epic end to the decade of turmoil that surrounded Napoleon Bonaparte’s stunning rise to power. Through a series of military victories across Europe that threw the Continent into disarray, Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of France (1804) and King of Italy (1805). A coalition consisting of much of the rest of Europe finally managed to topple his rule in 1814, exiling the former emperor to the island of Elba, and restoring King Louis XVIII to the French throne. After only 10 months of captivity however, Napoleon escaped and was embraced by the French military, who restored him to rule.

The time that followed Napoleon’s escape from Elba would become known as the “Hundred Days.” While Bonaparte moved to regain control of the large portions of Europe that he had conquered during his first run as Emperor, other European powers acted swiftly to contest his power grab, rallying 600,000 troops within days. Bonaparte took the offensive in an effort to divide the Prussian and British armies by moving into the lands that now comprise modern-day Belgium. He managed to surprise the Prussian army led by Prince Blucher as they were marching to join the Brits. This success on June 16, 1815, known as the Battle of Ligny, motivated the French troops and forced the Prussians to retreat. The majority of Napoleon’s forces then moved to support the attack on the British army, which was retreating toward Waterloo.

Napoleon planned to attack the British, led by the Duke of Wellington, at Waterloo before the Prussians could arrive to provide support. While Wellington was reportedly awake and organizing his troops by 6am on June 18, Bonaparte’s actions that morning are the subject of controversy. What is not disputed is that the French forces got a “late start,” beginning their attack on the British positions somewhere between 11am-1:30pm. The cause for this delay is debated. Tradition holds that terrible weather had left the ground sodden, which would have made artillery movements very difficult if not impossible. Another possibility, however, is that General Bonaparte himself was suffering from a serious illness which impaired his judgement.

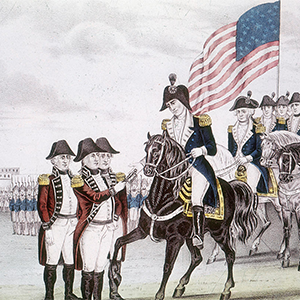

Napoleon exiled to the island of Elba

Wikipedia

Napoleon exiled to Saint Helena

Wikipedia

Could Napoleon’s longstanding urinary difficulties have swayed the course of history?

The French leader was known to have suffered from urinary complaints. He and many of his soldiers reported urinary problems during the Egyptian campaigns in 1798, possibly schistosomiasis. As early as 1810, his physicians had noted that Napoleon had bouts of urinary retention lasting up to 24 hours. Several sources suggest Napoleon was in throes of a serious urologic infection, possibly even urosepsis, during the Russian campaign in 1812. He had a fever, was passing sediment in his urine, and complained of severe dysuria and retention. Experts theorize this illness led to Napoleon’s failure to capitalize on his victory at the Battle of Borodino, allowing the Russian army to regroup and eventually, with the help of the long cold Russian winter, force the retreat of Napoleon’s forces.

Did these same symptoms plague the Emperor of France at Waterloo?

Such suggestions stemmed from observations of Napoleon’s officers as well as letters to his brother Jerome, who commanded a division of the army. These sources state that Napoleon fell back asleep at his table after breakfast on the day of the Battle of Waterloo, having perhaps taken laudanum to dull the severe pain of dysuria from cystitis, and had to be roused at 11am. Napoleon had appeared ill since the day before, prompting one of his generals, Vandamme, to say that "... the Napoleon that we have known no longer exists ...our success of yesterday will not have any future results.” Jerome Bonaparte around the time of the battle stated that his brother was suffering “a little weakness of the bladder,” but later confessed to a historian, a Monsieur Thiers, that he had been embarrassed to say at the time that Napoleon’s main complaint was hemorrhoids, which also plagued him for decades. There is of course a possibility that these two complaints could be linked and simultaneous, if chronic struggles to urinate led to prolapse of hemorrhoids. Either of these conditions, cystitis or inflamed hemorrhoids, could have made it very painful for the Emperor to ride his horse and command his troops, as some sources suggest he did less of than usual on June 18, the day of the Battle.

Whatever the cause, Napoleon’s dominance in Europe came to a stunning end in 1815, as he “met his Waterloo” and was defeated by the Allied troops that day. He abdicated and was exiled to Saint Helena, where he later died at age of 51 of advanced stomach cancer.

Even world leaders who seem invincible are subject to common human medical conditions!