From Battlefield Evacuation to Bladder Evacuation: Spinal Cord Injuries

Kevin Pranikoff, MD

An Ailment Not To Be Treated

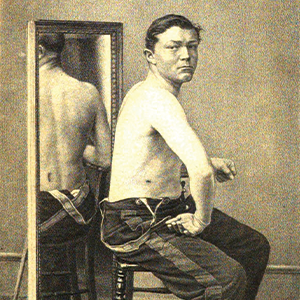

Spinal Cord injuries had such a poor prognosis before the mid-twentieth century that - since ancient times - they were generally approached as an ailment not to be treated.

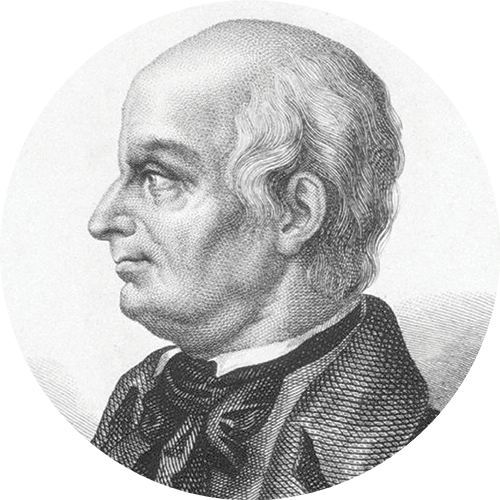

Lord Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) at the Battle of Trafalgar, Oct 20, 1805 received snipers’ bullets to the chest and spine. Nothing could be done for him.

General George Patton (1885-1945) sustained a spinal cord injury in a motor vehicle crash only months after the conclusion of the war in the European theater. He knew there was no cure for the injury (an ailment not to be treated) and refused all treatment. He was reported to have died of cardiovascular complications while still hospitalized.

Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson,

(1758-1805)

Wikipedia

George S. Patton (1885-1945)

Library of Congress

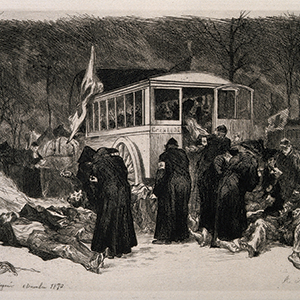

MASH Evacuation

National Library of Medicine

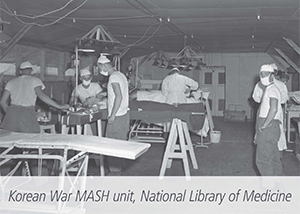

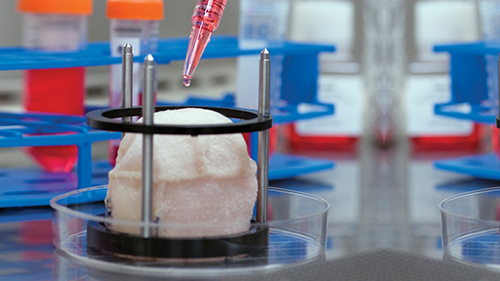

MASH Units

After witnessing their effectiveness in transporting downed pilots in 1950, General Douglas McArthur determined that helicopters should become part of wartime medical units. The workhorse became the Bell Aircraft’s H-13D made in Buffalo, NY; it allowed spinal cord injured patients to get care more quickly and thus survive. This placed pressure on our military, veterans’ and academic healthcare systems to determine how to care for these injuries and the patients who have them.

National Spinal Injuries Center

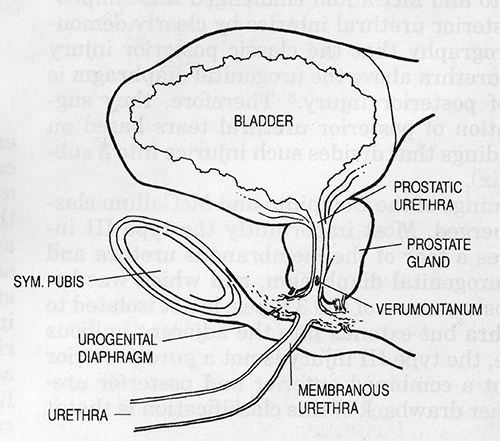

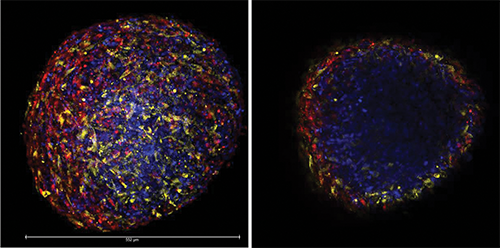

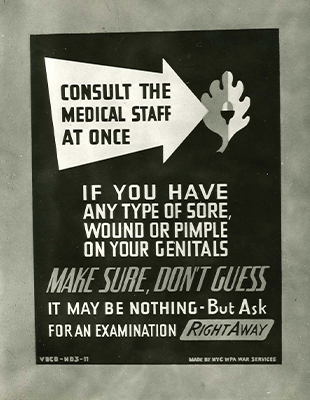

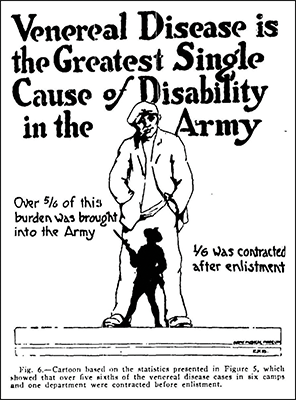

At the outset, renal disease, largely as a result of their urologic status, was the most common cause of death of these patients.

In 1944, the National Spinal Injuries Center at Stoke Mandeville Hospital was set up to treat World War II injuries. Sir Ludwig Guttmann (1899 – 1980), a Jewish neurosurgeon, revolutionized the care of these patients. He introduced a sterile, no-touch technique of intermittent catheterization for his patients that was very successful but also very resource- and time-intensive.

In the initial survival data from Stoke Mandeville (1943-1972), the urinary system is listed as the number one cause of death, responsible for 22% of deaths during that time period. For the 1973-1990 time period - a more fully mature period for modern neurogenic bladder management - the urinary system fell to number four, causing only 9% of the deaths.

From Soldiers to Civilians

Ernest “Pappy” Bors, M.D. (1900-1990) joined the staff of the first US spinal cord injury center at Birmingham General Army hospital (now Long Beach VA) in 1944. Although Bors and his partner, Estin Comarr, attempted to institute Dr. Guttmann’s protocols at the Rancho Los Amigos Rehabilitation Center, they were unable to afford the staff and supplies. So they initiated non-physician-performed catheterizations for quadriplegics and self-catheterization for those who were able. They dispensed with gowns and masks but continued sterile technique with comparable outcomes.

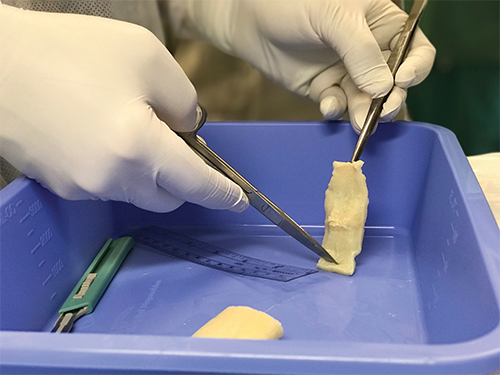

In 1972, Drs. Jack Lapides, Ananias Diokno and others at the University of Michigan reported on their experience with clean intermittent self-catheterization based upon Dr. Lapides’ theory that it is not the bacteriuria to fear, but rather retention and bladder distention that must be prevented. This mode of therapy has now become the worldwide standard, not only for neurogenic bladders but for the many neobladders or urinary pouches constructed for patients with nonfunctional or surgically-removed bladders.

Dr. Edward McGuire, studying patients with spina bifida at the Yale University School of Medicine, demonstrated that those with a urethral leak point pressure greater than 40 cm/H2O had a greater likelihood of upper tract deterioration than those with lower pressures. He subsequently demonstrated that utilizing clean intermittent catheterization, as proposed by Lapides, and maintaining bladder storage pressure - with anticholinergics if necessary - at under 40 cm/H2O is safe management for spinal cord injury patients with neurogenic bladders.