Samuel W. Jones, the paternal grandfather who bought his freedom on the “installment plan,” shown with his wife, Eloisa, and two of their children, Samuel L. (Dr. Jones’s father, at top) and Frank (c. 1870).

Dr. Richard Frank Jones (1898-1979), former Medical Director of Freedmen’s Hospital,

was Professor of Urology at the Department of Urology at the College of Medicine at Howard University, Washington, D.C., and the first Black Board-certified urologist in

the United States.

In 1978, the AUA Forum on the History of Urology, started by Drs. Frank Bicknell and Elmer Belt, invited Dr. R. Frank Jones to speak. The following quotes are from his presentation, published in 1981 by the AUA and Hoffman-LaRoche, Inc.

“If I have been persistent, inventive and dedicated, the credit accorded me is not fully mine. It truly belongs to two incredible men who were my earliest recorded ancestors: Robert Gunnell, a slave in Virginia; and Samuel W. Jones, a slave in Maryland. Both men achieved freedom and moved toward economic and cultural substance some two decades before the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. It was they from whom I inherited the spiritual, economic and cultural standards which unmistakably held me to my purpose.”

Samuel L. and Mary Payne Jones - Parents of R. Frank Jones, MD

“My entire formal education was obtained in the public schools of the District of Columbia and at Howard University…In the summer following my second year at Howard, I worked as a waiter in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. When I returned to Washington, my father arranged to have me hospitalized on a between semester date for what was thought to be an inguinal hernia but was actually a varicocele. I spent 14 days in the hospital completely fascinated by what went on! Luckily, following my return to school, there was enough time to take the biological sciences required to qualify for medical school in the fall of 1917.”

Fun Fact: Dr. R. Frank Jones’ grandmother Eloisa Benson was indentured to a “doctor” who taught her midwifery skills. “She was proficient at her calling and in demand locally as well as in other states. She traveled, for example, to Cincinnati and Chicago to deliver the babies of Charles Howard and his brother, General Oliver Otis Howard, most notably known as the founder of Howard University in 1867.

“From the beginning I was successful in my medical studies. Between the end of my junior year and graduation, I lived in a surgeon’s scrub suit and was available to any surgeon as second or third assistant for all kinds of operations at any time that did not conflict with medical courses and lectures (then generally given in the afternoon).”

“It was also at that time [1930] that I was given the choice of becoming either a gynecologist or a urologist. I chose urology.”

“Although Negro community hospitals existed in Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia and Baltimore, no residency training programs in urology had been undertaken at those hospitals. Until 1936 or 1937, when I instituted a four-month program for assistant residents in general surgery, there were but four black men in America who had received any formal training in urology.”

“To be accepted for Board evaluation in 1936, it was necessary to get endorsements from two local [Board-] certified members… Despite the prevalent venom of that day, I was examined with other urologists from this area. Nine of us were successful in becoming Diplomates of the Board that year (1936).”

Board Certified in Urology

Clinical Assistant Professor in Urology

Instituted a Training Program for Urologic Residents

Clinical Associate Professor in Urology

Clinical Professor in Urology

Training Program Approved for Urologic Residents

Medical Director of Freedmen’s Hospital

The American Medical Association (AMA), founded in 1847, espoused in its Code of Medical Ethics the tenet that scientific accomplishment alone should qualify membership. However, in routine practice, members uniformly opposed Black physician membership and interactions professionally or socially, and only by the 1940s did AMA-constituent societies allow occasional membership to Black physicians.

In response to the exclusion from AMA-affiliated societies, Black physicians founded their own medical societies, both locally and nationally. At the national level, the first minority medical association was the American Medical Association of Colored Physicians, Surgeons, Dentists, and Pharmacists, formed in 1895, although its name was changed in 1903 to the National Medical Association (NMA). Such organizations have served to support Black physicians and promote the welfare of all racial populations in America.

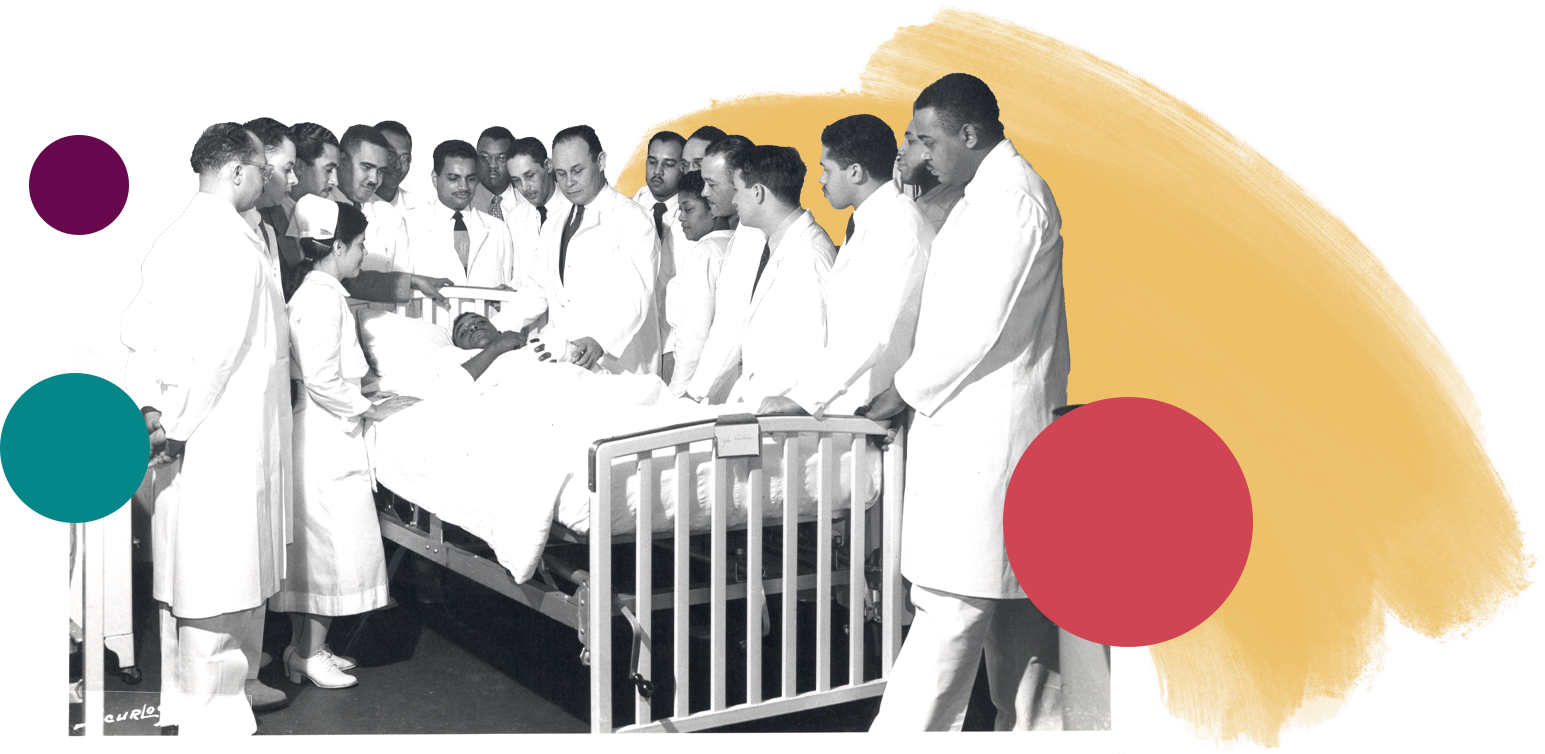

Members of the R. Frank Jones Urological Society

The Urology Section of the National Medical Association adopted the name of the R. Frank Jones Urological Society (RFJUS). The Society was incorporated as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation in 2009. It is dedicated to increasing the number of culturally responsible Black Urologists who excel academically, succeed professionally, and positively impact the community.

onward and upward: “As I reflect upon my modest contributions to medicine, to urology and to my medical school during a lifetime of racial discrimination, I can take comfort in the much wider opportunities we helped to forge for the present and future generations of black physicians.”

“Years later, in 1973, I entered the AUA golf tournament and won the much - coveted Golden Cystoscope, which I donated to the College of Medicine of Howard University.”

“The year after I was certified, I applied for membership in the Mid-Atlantic Section of the AUA - a prerequisite for AUA membership.”

“After the Mid-Atlantic meeting, I was notified that I had been elected to membership. I immediately sent $25 for the initiation fee, then proceeded to get endorsements from Dr. Harry Rolnick, and from Dr. Guy Hunner of Johns Hopkins University. Case presentations were delivered posthaste to the AUA and approved. About three weeks after the [annual] meeting in Quebec, I was shocked to receive a letter from the secretary of the Mid-Atlantic section stating that my acceptance for membership was faulty because I did not have the necessary endorsements. At intervals thereafter, I applied directly for a membership application. I never received one. Thirty years later, in 1965, when the atlarge category was established, my application was accepted directly into the AUA. I am now pleased to be a member of the American Urological Association!”

Download Full Chapter