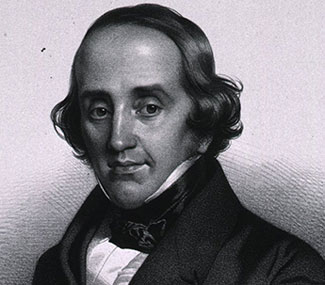

Jean Civiale, a surgeon in Paris, worked much of his life to treat bladder calculi. In 1818, he designed an instrument with a flexible sac attached that was designed to trap the stone that could be passed into the bladder. With the stone safely captured within the sac, he then injected chemicals into the sac to dissolve the stone. He quickly realized that stones would not respond to such treatment, particularly not to a single type of dissolving fluid.

He developed an instrument that he hoped would allow him to obtain pieces of stone for chemical analysis. This instrument consisted of a sheath through which prongs could be inserted into the bladder and grasp the stone. Between these prongs was a hidden drill that could drill out a small portion of the stone to be removed for analysis.

At the same time, others were busy developing instruments to treat stones; Leroy d'Etiolles developed his lithoprione, which trapped a stone. Also in 1822, Amussat showed his brise-pierre, which employed a rotary bur to fragment the stone. Both instruments were inadequate. A year later Civiale had abandoned his attempts to dissolve bladder stones and found his lithontripteur to be sufficient in dealing with bladder stones. This instrument, which could be inserted into the bladder, contained three prongs to grasp a stone in a straight shaft and a central drill driven by a bow. The instrument could grasp and re-grasp the stone and drill holes from different angles until the stone was fragmented and the pieces could be extracted with urination.

After some dispute, credit for the development of the first instrument to break a stone in the bladder of a living patient was given to Civiale. He received an award from the French Academy of Sciences of 6,000 francs in 1826 and the 10,000 franc Montyon Prize in 1887. Opponents of his instrument were labeled by Civiale as "butchers without the necessary delicate touch" who therefore insisted on using the old-fashioned perineal lithotomy. Civiale's instrument was tried in the United States as well, but it did not survive the test of time, as it was difficult to use and even more difficult to repair. Civiale made a generous donation to the Hospital Necker for an allotment of beds and thus founded the world-famous urological clinic at this hospital. A deplorable lecturer, he made up for this lack of skill by his famous books. His long history of successful bladder stone operations was marred only by his failure to crush the stone of King Leopold.

Civiale revolutionized the approach to bladder stones. His instrument, however, was soon superseded by Heurteloup's percussion lithotrite, which paved the way for later crushing lithotrites.